|

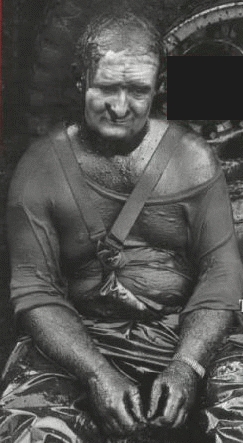

| This boy, of course, was dead, whatever that |

| might mean. And nobly dead. I think we should feel |

| he was nobly dead. He fell in battle, perhaps, |

| and this carved stone remembers him |

| not as he may have looked, but as if to define |

| the naked virtue the stone describes as his. |

| One foot is forward, the eyes look out, the arms |

| drop downward past the narrow waist to hands |

| hanging in burdenless fullness by the heavy flanks. |

| The boy was dead, and the stone smiles in his death |

| lightening the lips with the pleasure of something achieved: |

| an end. To come to an end. To come to death |

| as an end. And coming, bring there intact, the full |

| weight of his strength and virtue, the prize with which |

| his empty hands are full. None of it lost, |

| safe home, and smile at the end achieved. |

| Now death, of which nothing as yet - or ever - is known, |

| leaves us alone to think as we want of it, |

| and accepts our choice, shaping the life to the death. |

| Do we want an end? It gives us; and takes what we give |

| and keeps it; and has, this way, in life itself, |

| a kind of treasure house of comely form |

| achieved and left with death to stay and be |

| forever beautiful and whole, as if |

| to want too much the perfect, unbroken form |

| were the same as wanting death, as choosing death |

| for an end. There are other ways; we know the way |

| to make the other choice for death: unformed |

| or broken, less than whole, puzzled, we live |

| in a formless world. Endless, we hope for no end. |

| I tell you, death, expect no smile of pride |

| from me. I bring you nothing in my empty hands. |